Let's be real: Salary transparency is complicated

Sometimes, talking about money can make us feel weird.

Yesterday was my least favorite holiday of the year “Equal Pay Day.”

In 2019, I co-hosted a Money Diaries podcast with the wonderful Paco De Leon (buy her book—it’s one of the best personal finance books out there). Over the course of seven episodes, we talked to a variety of people about their financial experiences (including

of Downtime). It was a fun time, and I loved every minute of it. Well, except for one bit.Our producer wanted me to reveal my salary during the final podcast. At the end of each episode, Paco and I would run through the credits, Paco would introduce herself, then I would introduce myself, and then one of us would share a little personal money fact. If you didn’t listen to the very end of the episode, you would have totally missed it. And how many people actually listen to the very end? (I honestly have no idea!)

The producer argued that since we had just interviewed all these women who shared their salaries, I should do the same. I agreed, and we recorded a version of the podcast with me saying, “I’m Lindsey Stanberry, the work and money director at Refinery29, and my salary is $125,000 a year.”

But then I wimped out. I got really nervous about sharing that information with the world. I was in the middle of interviewing for new jobs, and we all know what a dance salary negotiations can be. I didn’t want hiring managers to know my current salary and use it against me. (I know they sometimes ask, but honestly, I would always inflate it a bit. Doesn’t everyone do that?)

I also was worried about my R29 colleagues finding out what I earned and having feelings about it. I had no idea what my fellow directors made, and I didn’t want to create any drama. So I begged the producer to let me re-record the ending, and in that final sign off, I shared that I spent $90 on private pilates sessions every week. Kinda lame, I know.

Perhaps loyal Money Diaries fans think I should be more forthcoming with my salary information (both then and now), since over the years, I’ve interviewed hundreds of women about their financial situations. And you might have a point. But at this moment in time, I don’t think I’d ever share my salary publicly. If we’re hanging out one on one, well, that’s a whole different story…

Salary transparency is a complicated beast. It essentially exists on three levels.

One, on a personal level, where we have private conversations with friends, colleagues, partners, parents, etc. about how much we earn.

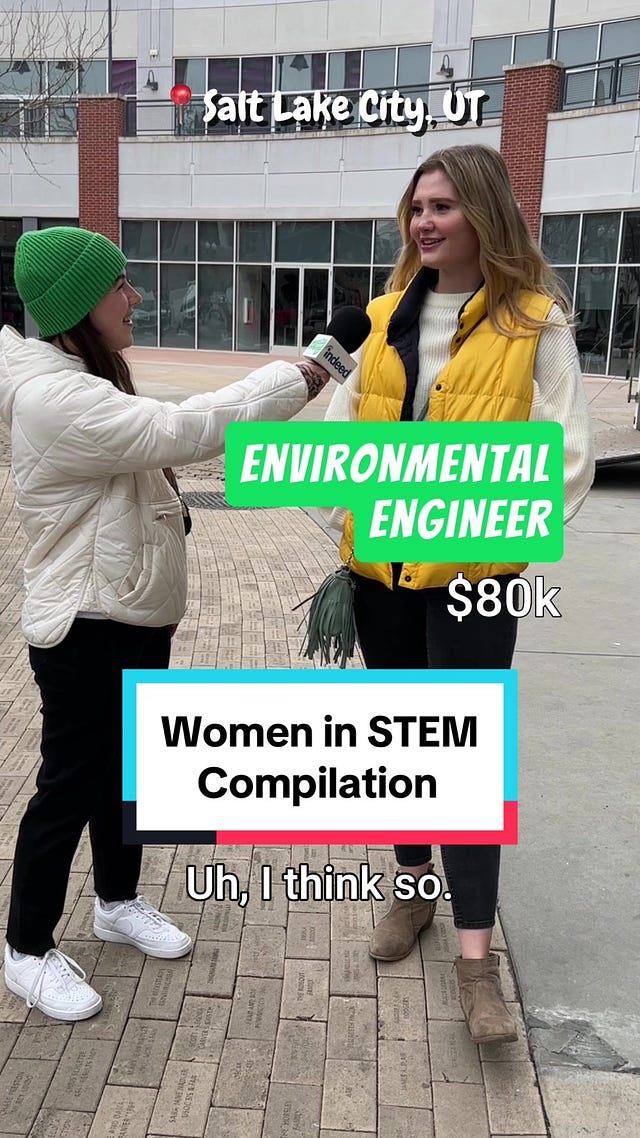

Two, on a personal but public level, with more and more people openly sharing salary information on social media and in newsletters. See Leslie Stephen’s fascinating Substack about what she earns and how she budgets, the TikTok phenom Salary Transparent St, and this Reddit thread on salary transparency (great comments on this thread, too!).

And three, on the corporate and government level, where businesses are increasingly required to post salary ranges in job listings (now a law in four states) and/or share salary data (a thing in California, the U.K., and Australia).

Salary transparency can be weird on all three levels. It can be uncomfortable to discuss your salary with your friends, coworkers, or even your partner (see my response to a Diem question in this week’s Things We Don’t Talk About newsletter). Opening up about your finances on a public platform invites all kinds of scrutiny (especially when you’re a woman—just look at the comments of the first edition of Home Economics). And implementing salary transparency in the workplace can be an incredibly difficult, costly, and time-consuming process.

Last year, I moderated a panel on the topic at the Fortune Most Powerful Women Next Gen conference. The panel included an incredible group of women—Nakia McKenzie (AARP), Kate O’Connor (H&R Block), Tali Rapaport (Puck), and Courtney Robinson (Block)—each of whom has been working within their organizations on pay transparency and pay equity policies. And they were very transparent (ahem) about how much work it takes to institute these policies. But they also agreed that it’s essential if we want to close the gender wage gap.

“Pay transparency starts with wanting to achieve pay equity,” said Nakia during the panel. Over three years, Nakia and her team at AARP spent a tremendous amount of time standardizing jobs. Like many companies, they had people doing the same work with different job titles and earning different salaries. During the process, they went from having 1,300 individual jobs for 2,000 people down to 500 jobs. After standardizing the job descriptions, they instituted salary ranges based on the market but also on internal equity, she explained.

Despite all this work, AARP doesn’t include salary ranges for most of its job listings online. Scrolling through its careers page, you’ll only find the info on remote roles. If you’re applying for an AARP job in D.C., where the non-for-profit is based, you probably won’t learn the salary range until you get on the phone with a recruiter. And when they choose to share that information is up to their discretion, Nakia said during the panel.

Of the few job listings with compensation info posted on the AARP career site, the salaries listed usually fell within a $20,000 range. This is worth noting because since the law rolled out in New York City in November 2022, people have been quick to point out that some companies skirt the requirement by offering ridiculously wide salary ranges. CBS News reported on a Wall Street Journal listing for a head of news audio role with a salary range of $140,000 to $450,000. What are you supposed to do with that info? The New York Times reported that higher-paying jobs tend to have the widest salary ranges.

“The devil is in the details in terms of how people implement these policies, and if companies take it seriously, or if they just see it as a box they have to check,” says Dr. C. Nicole Mason, president and CEO of Future Forward Women, a women-focused legislative exchange and policy network. (Also worth noting: Nicole coined the term “shecession” in 2020.)

While they’re not perfect, salary transparency laws hold companies accountable, Nicole argues, and allow them to begin to ferret out pay inequity.

When Nicole was president and CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), she spent nearly a year rolling out compensation schemes, clearly detailing why each job paid what salary based on the role, the employee’s education and experience, and other factors. And then IWPR published the information online, giving employees—and potential employees—the chance to understand the organization’s compensation structure.

Obviously, this was very important work for an organization like IWPR to do—they needed to walk the walk. But not everyone was happy with the results. Because here’s one of the secrets about salary equity that few people want to talk about: Sometimes, you’re going to be at the top of your salary band, and as a result, you’re not going to get a raise.

In Nicole’s case, there were a few staffers who made more than the salary range for their job titles. As a result, they were informed that it would be a few years before they received another raise. If you’re a high performer, that can be a bad feeling, knowing you’re locked into a salary in the name of equity, and there’s no room for monetary growth. And if you’re a manager of a high performer who’s threatening to leave for a job with better pay, and you work for a company with strict salary bands, you might be unable to give your star employee the raise you think they deserve.

(Bear with me for a moment for a brief tangent—I know this newsletter is already too long. I keep thinking about how when we start our careers, the goal is always to earn more and more and more money, and we are led to believe that how much we earn is correlated with how good we are at our jobs. It’s easy to get caught up connecting net worth with self worth. But at some point you will hit a ceiling, and you might not be able to earn more. This is obvious if you’re a teacher or working in some other unionized job, but I think it’s often less discussed in the creative and tech fields. Salary schemes may lead to pay equity, but they will also lead to salary ceilings. And in order for us to not feel really, really bad that we’re not getting a big raise every single year, we probably need to take some time to reflect on how much we really need to earn to live our lives—aka what is enough—and figure out how to feel good about the work we do regardless of salary, assuming that we are fairly paid. )

While salary transparency laws are relatively new in the private sector, the federal government (and state and local governments) publicly posts the salaries of all government employees in the name of accountability. You can easily google to see how much the head of the Cincinnati Department of Parks makes ($171,865.80) compared to a full-time florist in the same department ($52,674.21). (Side note: Florist for the city parks sounds like a really fun job.)

I know it might make some people squirm to think about their salaries being viewable on a public website, but the idea gives me a sense of relief. Just imagine you’re applying for a job in the public sector, and you can easily look up salaries of similar roles, as well as the salaries of your boss, her boss, and all her direct reports. Incredible! I’ve never known what my boss makes. Have you?

I’ve hired more than a dozen people over the years, and I find the salary negotiation piece of it to be the absolute worst. Part of the reason I dislike it so much is precisely because companies are always so opaque with salary info. Oftentimes, I was just given a number with no sense of how it fit into the overall budget. And everyone would have lost their minds if I simply shared with a potential hire just how much their counterparts made. Yet it would have been so much easier if I could have just said, “All my senior reporters make $100,000, so I’m offering you $100,000. Take it or leave it.”

By publicly sharing salary information—at the very least in job listings but ideally across organizations—employees are able to educate themselves about what their jobs are worth. And that’s hugely powerful.

“When there is transparency, when there is clarity, women win,” says Nicole. Salary transparency laws “benefit women and help to close the pay gap in companies,” she adds.

Unfortunately, these laws aren’t a cure-all. There is still a 5.6% gender wage gap among federal workers, and (not surprisingly but depressingly) it’s even wider for women of color. There’s a gap of 15.5% for Black women and 27.2% for American Indian and Alaskan Native women. But the federal wage gap is still 16% smaller than what you see in the private sector.

One of the reasons why salary transparency can’t completely fix the wage gap is because of discrimination and our unconscious bias, says Meggie Palmer, equal pay advocate and founder of the app PepTalkHer. She points out that there have been studies that show little girls earn smaller allowances than little boys. The chores assigned to little boys—Meggie gives the example of collecting firewood—are perceived as “tougher work” than those frequently assigned to little girls (like helping prep dinner, she says). It’s not that parents are trying to be unfair, she argues—they’re just unconsciously assigning higher pay to jobs they typically give to boys. We are simply products of our environments. Unfortunately, as a result, from a young age, girls understand that their work is worth less, Meggie says. Oof.

But Meggie is hopeful things are changing. In part because it seems like Gen Z and younger millennials appear to be much more open about their money than past generations were. They are growing up seeing people openly share their salaries on social media, and they feel more comfortable sharing their salary info one on one. They also expect companies to be more transparent.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

It’s also important to remember that compensation conversations don’t end once you get the job. So often we’re just eager to get an offer, and we don’t think enough about the career path this role might offer. Nicole encourages applicants to ask recruiters and hiring managers for more information about organizational culture, company philosophy on pay equity, and whether there are salary transparency policies in place or being developed.

“I’ve never been asked that question in an [job] interview before,” says Nicole, but we both agree it would be exciting to hear it. And if the hiring manager doesn’t have an answer, it’s an opportunity for them to go back to HR and share the experience, hopefully sparking internal conversations, says Nicole.

Of course, this kind of work requires a ton of emotional labor. It’s not lost on me that Nakia and Nicole are Black women who are driving change. And it’s a lot to ask women and people of color to bear the burden of pushing for equity. I lamented to Meggie that I sometimes worry these conversations happen in an echo chamber. Women sharing compensation information is great, but it would be even better if men would also share, because they are ostensibly the ones earning more.

Meggie agrees—more allies are always better. But she also points out that we all could be better allies.

“The overall pay gap is shocking,” she says. “But the pay gap for Black women is appalling. With all movements, we have to start somewhere, and typically, it’s the echo chamber where we start because that echo chamber gets louder and louder and louder before it shatters and disseminates more widely through society.”

I love this idea of the echo chamber shattering and the movement growing. I want to believe that one day we won’t unconsciously assign so-called “girl” jobs and “boy” jobs different values. And I hope we’ll reach a point where we all feel comfortable talking about salaries because that information is already public and easily accessible. I know Meggie is right that we have to start somewhere, and we have to keep talking until we see real change.

So let’s talk! How do you feel about salary transparency? If you’re a hiring manager, how do you handle the negotiating process? Do you discuss money with friends, family, loved ones? I want to know!

And in an effort to get paid for the work I do, I’ve also decided (with a little pep talk from Meggie!) to turn on the paid option on this Substack. All newsletters will continue to be free, at least for the time being, and at some point, I will offer something special for paid subscribers (add it to my endless to-do list!). But if you want to support me and my writing, you now have the option. I appreciate it!

Thank you so much, Lindsey, for your thoughtful writing.

As a state university employee, I value the salary transparency available through state salary registries; however, I've found that my salary is consistently underreported on those sites, leading me to wonder if others' salaries are also deflated. It can also be jarring to see that my supervisor makes nearly $100,000 more than me, and her supervisor makes another $100,000 more than that. It’s true that the expectations demanded of their positions are certainly much greater than that of my own, so I don’t begrudge their salaries. It’s just interesting to know how much they make. When I’m having a more frustrated moment it can be easy to unjustly think, “Is their work worth that much?” (Not that I could do what they do ;)

Salary transparency can also be tricky when other factors come into play. In my office, we are a mix of customer service geared employees and "knowledge workers" (My apologies to Cal Newport, but I kind of hate that term because everyone uses knowledge to successfully complete their work). Not only is there a wide salary gap between people sitting mere feet apart, but there is also a difference between those who can work remotely and those who must be in their seats all day Monday through Friday. I understand that these differences are the result of pay scales that exist across the University, which often have different education requirements; however, it can make for uncomfortable moments when some individuals, myself included, work remotely and/or have flexible schedules, while also enjoying nearly double the salary of others. There can be a feeling of wanting to prove how hard I’m working, potentially in part because my work is not as obvious as the work of my peers, whose work is more robust quantitatively, and who have a systematic audit trail for their administrative work. Having recently hired two employees, it was also difficult to not be able to negotiate within a tight pay schedule. I applauded one employee’s effort to negotiate--this is especially important in an environment where consistent cost of living adjustments can grow one’s salary overtime and salary transparency makes one's starting salary important when later transitioning to different roles within the University--but in the end, I had nowhere to go. It can also be demoralizing to employees when they know that for their specific role, the salary is and will remain what it is.

On a completely separate note, what are your thoughts on salary transparency with children? My two kids are 7 and 10 and as a family we often talk about spending and saving money, and how to make money decisions in general. When they ask how much I make, I’m hesitant to respond. I don’t want them to tell their friends (their school has some very well-off families and some families who struggle financially), and I’m not sure if they would have any concept of what the amount actually means. Sure, it sounds like a big number if you have no idea what retirement, mortgages, and childcare actually cost. We live so frugally that sometimes I worry they think we are not doing well financially, when in reality we have significant investments. On the other hand, I want my daughter, especially, to feel empowered to grow her career and be proud of her earnings. Would love to hear your thoughts!

Another fantastic piece (with classic Lindsey comments throughout!). I do talk about finances with my husband, friends, and other loved ones. But, that's a more recent thing. Early in my career, I felt pressure to 'name a salary' and in doing so (without a ton of pay transparency around at that time), I undersold myself. I wish back then I'd had exposure to pay transparency so I could ensure I was paid a better, more fair rate. I'm so glad this topic is getting much more traction and we're keeping it going. Thanks, Lindsey!